Rate limiting in Golang using rate package

Rate Limiting comes up quite often when working with web servers. As a Golang newbie(and working on Backend after a while), I had a chance to implement the rate limiter on the client side to not overwhelm the target server while generating the load.

In this post, I’m going to talk about the x/time/rate package and how to use it as a batch processor working in intervals.

How Limiter works

To work with the package, we need to create a Limiter. let’s briefly take a look at the definition:

A Limiter controls how frequently events are allowed to happen. It implements a “token bucket” of size b, initially full and refilled at the rate

rtokens per second.

This confused me quite a bit, so reading through the wiki about the Token Bucket algorithm helped me understand it better.

A simple analogy: You have a bucket that can hold 10L(total number of tokens). It has a knob that you can turn and it will let the liquid flow so the bucket has more room as time goes on. For this particular bucket, I will let the liquid flow 1L per second(rate). When the bucket is empty, we can pour down 10L at once, or if there were 3L in the bucket already, we can only add 7L to the bucket(burst) at once. After 1 second since the bucket was full, you will have another room for 1L, or you wait for 0.5s to pour 0.5L (r tokens per second or 1 token per 1/r second).

Limiter is an implementation of the above and lets you control how frequently the events can happen.

Set the Limit and Burst

Two parameters are needed when creating a new Limiter: rate and burst. The first parameter rate is Limit type which defines the max frequency of some events. Passing 1 means 1 event per second is allowed for the limiter. There’s a handy function that helps you calculate the rate when you have an interval rather than 1 second; rate.Every(t time.Duration). See examples below:

import (

"time"

"golang.org/x/time/rate"

)

func main() {

r := rate.Every(5 * time.Second) // 1 event per 5sec, r = 0.2

r = 2 * rate.Every(5 * time.Second) // 2 events per 5sec, r = 0.4

}

Now, you need to set the Burst size. Burst is the maximum number of tokens that can be consumed in a single call, in other words, n events can happen at once where n is the Burst size. So set this value that wouldn’t overwhelm the target server or protect your server from Ddos by setting the right burst size.

r := 2 * rate.Every(5*time.Second)

burst := 10

limiter := rate.NewLimiter(r, burst) // Limiter allows 10 events to happen at once and refill 2 tokens every 5 seconds.

Here’s a playground link of the bucket example from the previous section in the code. Have a look, play with it, and assert your understanding.

Use it to work like a batch processor with Interval

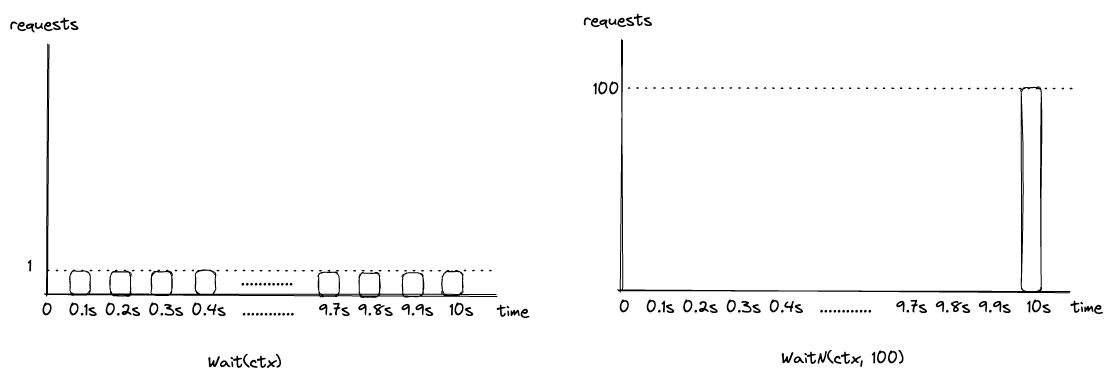

I had a task that required the limiter to send bursty events per interval while respecting the rate limit. As you can see from the above playground, I used lim.Wait(ctx) to wait for a token to be refiled so that I can send an event. This way, we can distribute the load evenly within a time duration, and it respects the event rate, so it kind of works. But for me, this wasn’t the case. I wanted to send n events every t interval without distributing the load. For this, you can use lim.WaitN(ctx, n). This block until n tokens are refilled so that you can send n events at once. the n of course should be smaller than Burst size, otherwise, it returns an error.

Here’s an example. I want to send 100 events every 10 seconds. the rate r = 10/s. If you use Wait(ctx), it will let you send 1 request every 100ms. Instead, if you use WaitN(ctx, 100), it takes 10 seconds to get the 100 tokens, so it will block for 10 seconds then you are allowed to send 100 events at once at the 10-second mark.

Conclusion

There are other strategies you could use when the events exceed the rate using Allow or Reserve method. The example above is the typical case where the events are enqueued when the available tokens are not enough. It’d be fun to apply different strategies to handle backpressure buildups or other cases of data flow possibilities.